How To Write Test Cases: A Step-By-Step Guide

Learn how to write effective, reusable test cases with step-by-step examples, best practices, and tools to improve software testing quality.

Many teams struggle to write effective and reusable test cases.

Poorly written test cases frustrate developers (and QA teams) who rely on them during the testing process. It’s a waste of everyone’s time.

A clear, well-structured test case does the opposite:

- it helps testers validate functionality, and

- provides developers with precise information to fix defects in software quality when tests fail.

In this article, I’ll explain how to write high-quality test cases and share a few best practices you can use right away.

What is a test case?

A test case is a detailed set of actions, inputs, and expected results used to verify that a specific part of a software application works correctly. This “detailed set of actions” provides clear instructions for how to test/validate one feature or condition.

The goal is to help testers find defects OR confirm that the software behaves as expected under pre-determined conditions.

Difference between test case vs. test scenario vs. test plan

These three terms are often used interchangeably, but they serve different purposes:

- Test case: A specific set of test steps, inputs, and expected results used to validate one function or requirement.

- Test scenario: A high-level idea of what to test, often written from the end user’s perspective. It’s a goal or functionality to validate. For example, a scenario is to “verify that the user can reset their password.”

- Test plan: A high-level strategy document. It outlines what to test, who will test it, when, and how, across the entire testing process.

Together, these components are the foundation of any structured software testing process.

Anatomy of a standard test case (with example)

A good test case should look like this:

A well-written test case follows a consistent structure.

It includes the information testers need to prepare, execute, and evaluate the test with accuracy, such as:

1. Test Case ID/Name

This is the unique identifier used to reference the test case. It helps testers, developers, and managers find and track the test during execution, reporting, or debugging. This can be as simple as TC001 or “TC_Login_001”, but the more descriptive the better.

2. Title/Description

The title briefly summarizes the purpose of the test case, while the description adds context. Context can include the feature that is being tested and what the test should validate.

For example, when the title is “Login with valid credentials,” the description can read “Verify that a registered user can log in successfully using a correct username and password.” It’s straightforward and specific.

3. Preconditions

Preconditions are what must be true or set up before the test. This includes system states, user roles, permissions, or any configuration required. For example, if testers need to log in with a specific username and password, you need to be sure that you’ve configured the backend to naturally accept the username and password.

4. Test data

This is the input values, files, or conditions the test uses. Test data helps simulate realistic scenarios so the test can be repeated consistently. For example:

- Username: “johndoe@examplemail.com”.

- Password: P@ssword123.

5. Steps to execute

This is a numbered list of actions the tester should follow. Each step should describe a single, clear action written in an imperative style. For example:

- Navigate to the login page.

- Enter valid email and password.

- Click the “Log in” button.

This way, they don’t skip anything while testing.

6. Expected result

This describes what should happen after the steps are completed. It sets a clear benchmark for whether the test passes or fails. For example, is the user redirected to the user dashboard? Is there a welcome message that reads “Welcome back, John” or another user-specific name?

Basically, it helps you understand what the user is supposed to see if the application/website is behavioring as expected.

7. Actual Result

This field is filled in during test execution. It records what actually happened after following the test steps.

8. Pass / Fail Status

This final field captures the outcome of the test based on the comparison of expected and actual results. If the software application did what is expected, the status would be Pass.

Now that you know what to include in your test cases, here’s a step-by-step guide to how to write them:

How to write a good test case

1. Understand the requirements

Each test case should serve a specific purpose. Before writing one, understand the user story and the friction they experienced. If you’re in the development phase and just wanted to validate a scenario, understand the requirement or acceptance criteria before you start writing the test.

This helps your test suite align with the actual goals of the feature being developed/improved. It also helps you validate whether the software meets business and functional needs.

The second factor you should consider is traceability. This is the ability to link each test case to its related requirement or feature, which is important during audits, release planning, or when bugs are reported.

If a test fails, traceability helps your team quickly understand which part of the system is affected and why the test existed in the first place.

2. Define preconditions and test data

Before executing a test case, testers need to know what must already be true. Preconditions describe the setup, environment, and system state required before the first step begins.

These details remove guesswork so testers are testing a system that’s actually supposed to provide an “expected result.”

Common preconditions include configured user roles, authentication status, application state, network conditions, or necessary data in the database. Without these, a tester that’s supposed to verify if they can log in as an admin won’t be able to do that.

So, provide the preconditions and test data of each test so your quality assurance testers can carry out the test without friction.

3. Write clear, simple test steps

Each test step should describe a single, observable action. Use clear, imperative language (a test typically starts with an action verb), and focus on what the tester must do, not what the system will do.

Also, avoid combining multiple actions in one step to reduce confusion. For example, a good test step would be:

- Navigate to the login page.

- Enter a valid email address (provided email address).

- Enter a valid password (provided password).

- Click the “Log in” button.

A poor test step would be:

- Try logging in as a valid user.

You see, it’s a vague instruction that’s open to many interpretations. Which user? What credentials? What does “try” mean in this context?

Lastly, avoid technical jargon, abbreviations, or internal terms that actual users may not understand. A well-written test step should be executable by anyone on the testing team, regardless of seniority or familiarity with the application.

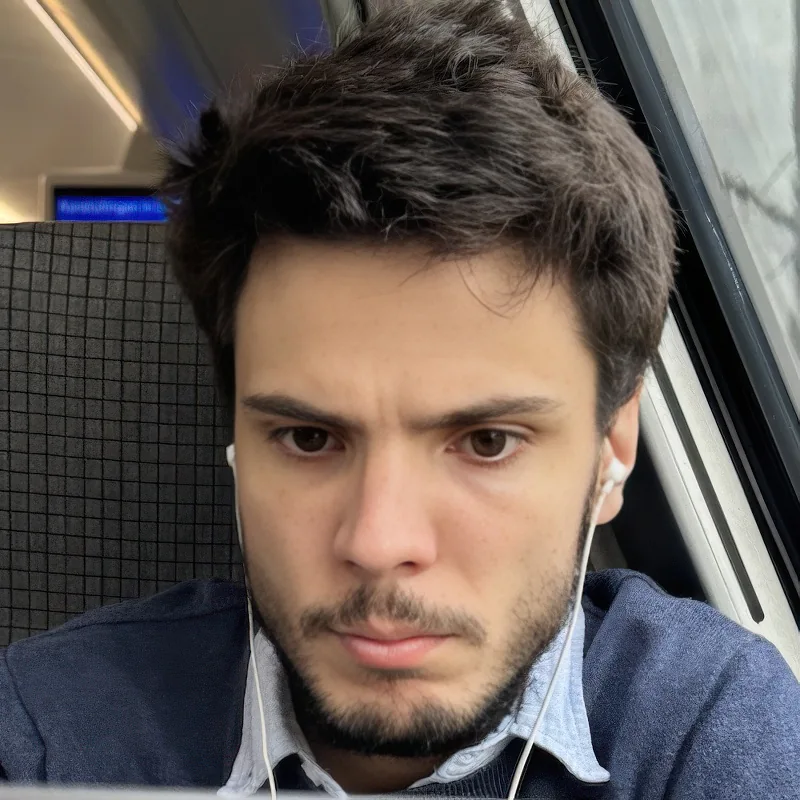

4. Specify expected results

Expected results describe what should happen after each test is executed. They act as the benchmark for determining whether the software passes or fails the test.

Keep this part specific, measurable, and unambiguous. Also, avoid vague outcomes like “Page loads correctly” or “Data is saved.” Instead, describe the exact behavior the system should produce.

For example, “System redirects to the user dashboard and displays the welcome message: ‘Welcome back, John.’”

The expected result can also be visual changes, URL redirects, database updates, confirmation messages, or API responses. It all depends on what you’re testing. The goal here is to leave no room for interpretation so testers know what a pass (or fail) looks like.

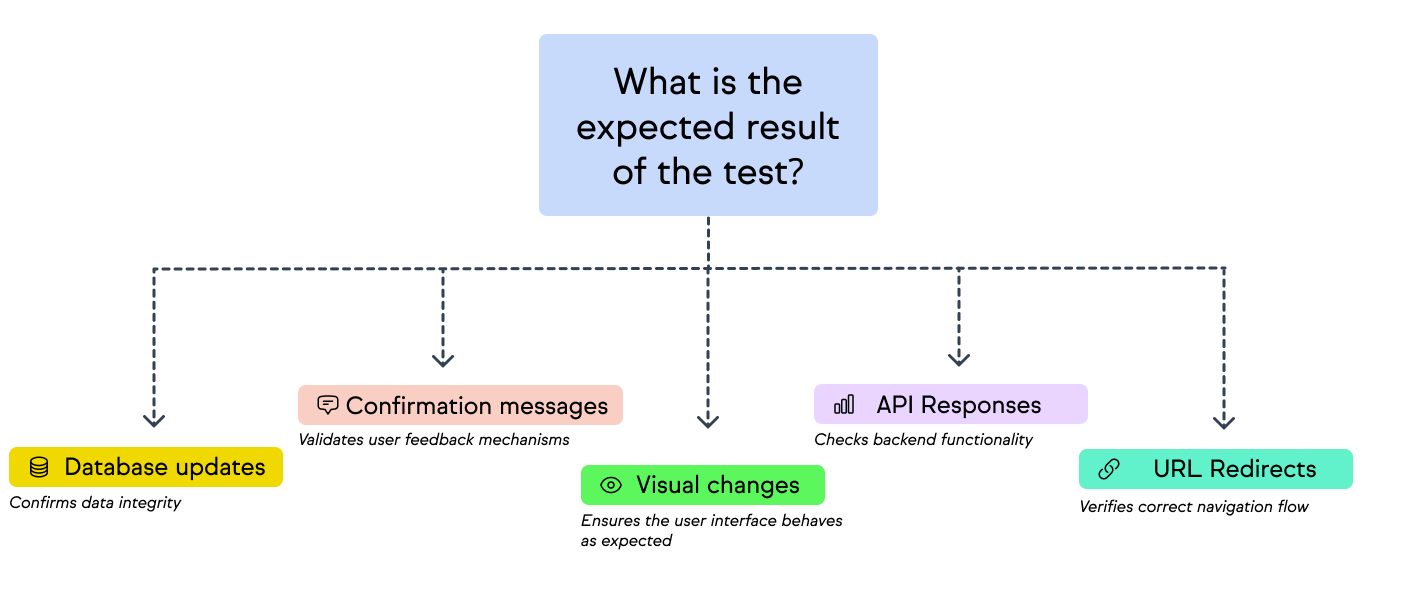

5. Review and reuse

Before you finish a test case, take the time to review it, ideally with someone else on the team. This can help you find unclear instructions, missed steps, or inconsistencies that can affect the testers during tests.

Also, after the test, review the results and tester feedback. If someone struggled to follow the test, or a developer asked for clarification while debugging, you need to revise the test case. It usually means someone didn’t understand the instructions and that may have skewed the result.

Finally, think about how your test case can be reused in other areas of the application. Some actions like logging in, submitting a form, or checking user permissions are recurrent in many different features.

So, instead of writing the same test steps over and over, create a dedicated test case for those common actions and modify it. For context, if you have a test case that checks “Login with valid credentials,” you can modify it for a test case on “change password”.

This approach keeps your test suite lean so you can replicate some processes without rewriting from scratch.

Best practices for writing test cases

The following practices can help your team improve how you write test cases:

1. Be concise but thorough

A good test case gives testers everything they need. No more, no less. Overly detailed cases can complicate the test while vague ones leave room for error.

For context, instead of writing “Enter your login details and try to sign in,” specify it:

- Enter email: qa.user@example.com.

- Enter password: Test@123.

- Click the “Log in” button.

It’s simple and straightforward.

2. Focus on the end-user perspective

Always frame your test case around how the end user will interact with the software. This helps you understand how your system responds to real users, not how you assume it will.

Case in point, if users want to search products by keyword, a good test case might include scenarios such as

- searching for an exact product name,

- a partial keyword, or

- a misspelled word.

This helps you try different scenarios to test the functionality of the “search” feature.

3. Cover edge cases

Edge cases show the defects that regular browsing paths miss. So, make sure your test cases account for both expected and unexpected behavior.

For example, when testing a payment form, write cases for valid credit card inputs, but also invalid ones. Include options like expired cards, incomplete numbers, or unsupported card types to know how the system will react.

4. Keep the language consistent

Use the same terminology, style, and formatting across all test cases. This helps testers execute cases faster and avoids confusion. For example, when you use the term “Click,” stick to it instead of mixing it with “Tap” or “Press.”

Also, stick to one format for expected results. For context, write “System displays [X]” rather than “You should see [X].” This helps the user know that the expected result is not from their end; it’s the system’s response to specific actions.

5. Regularly update test cases during iterations

This is self-explanatory: your software changes when you add other features, tweak a nuance, or remove an unnecessary step. When this happens, outdated test cases become liabilities.

So, review and update your test cases when you change your features or remove something irrelevant from your code.

6. Balance coverage vs. redundancy

Test coverage should be broad enough to validate critical functionality. At the same time, it should not be bloated with duplicate or overlapping cases.

For example, if you have a test case for the title “User logs in with valid credentials,” you don’t need five different versions. Instead, add edge cases into the mix like “invalid credentials” or “empty fields” to extend what test coverage.

Who writes test cases?

Test cases are usually written by QA engineers, since they validate software quality. In some teams, developers contribute to it by creating unit test cases or documenting steps for complex modules.

Product managers and designers also provide input when it comes to user flows and acceptance criteria. This is primarily to ascertain that test cases align with business goals and user experience.

In summary, everyone plays a role while writing test cases (especially in agile teams). The goal is for each test case to reflect requirements and support overall software quality.

Types of test cases

Each test type depends on the purpose of the test and the stage of the software development lifecycle. Types include:

1. Functional vs. non-functional

Functional test cases validate specific features and actions. For example, “Users can log in with valid credentials.”

Non-functional test cases measure qualities like performance, usability, or security. For example, “The system responds to a search query within two seconds.”

In other words, functional tests care about what users do, whereas non-functional tests care about what the system does (in response to user actions).

2. Positive vs. negative

Positive test cases check expected behavior when users act correctly (e.g. enters valid data).

Negative test cases validate system responses to invalid or unexpected input (e.g. user enters wrong data).

3. Smoke, regression, and exploratory test cases

- Smoke test cases quickly verify whether a build is stable enough for further testing.

- Regression test cases ensure new changes in features or paths haven’t broken existing functionality.

- Exploratory test cases allow testers to explore the system without predefined steps. They use intuition and experience to find defects in the software.

4. Automated vs. manual tests

Automated test cases are best for repetitive, high-volume scenarios like regression testing, API validation, or performance benchmarking.

Manual test cases are valuable for usability checks, exploratory testing, and scenarios that rely on human judgment.

Read more: Manual Testing vs Automation Testing: Comparison & Differences

Test case management tools

Test case management tools help you organize, track, and run test cases at scale.

Popular options include:

1. Jira: Originally a project and issue tracker, Jira can be customized with add-ons or issue types to manage test cases. It helps teams link test cases to requirements and defects so you can trace every test in a single platform.

We wrote more about how to write test cases in Jira here.

2. Zephyr: Zephyr integrates directly with Jira as a dedicated test management with features like test cycles, scheduling, and reporting. It gives QA teams a more structured way to manage both manual and automated tests.

3. qTest: qTest supports large-scale test management with features like advanced reporting, automation integration, and compliance tracking. It is often used in organizations that need detailed governance and audit-ready documentation.

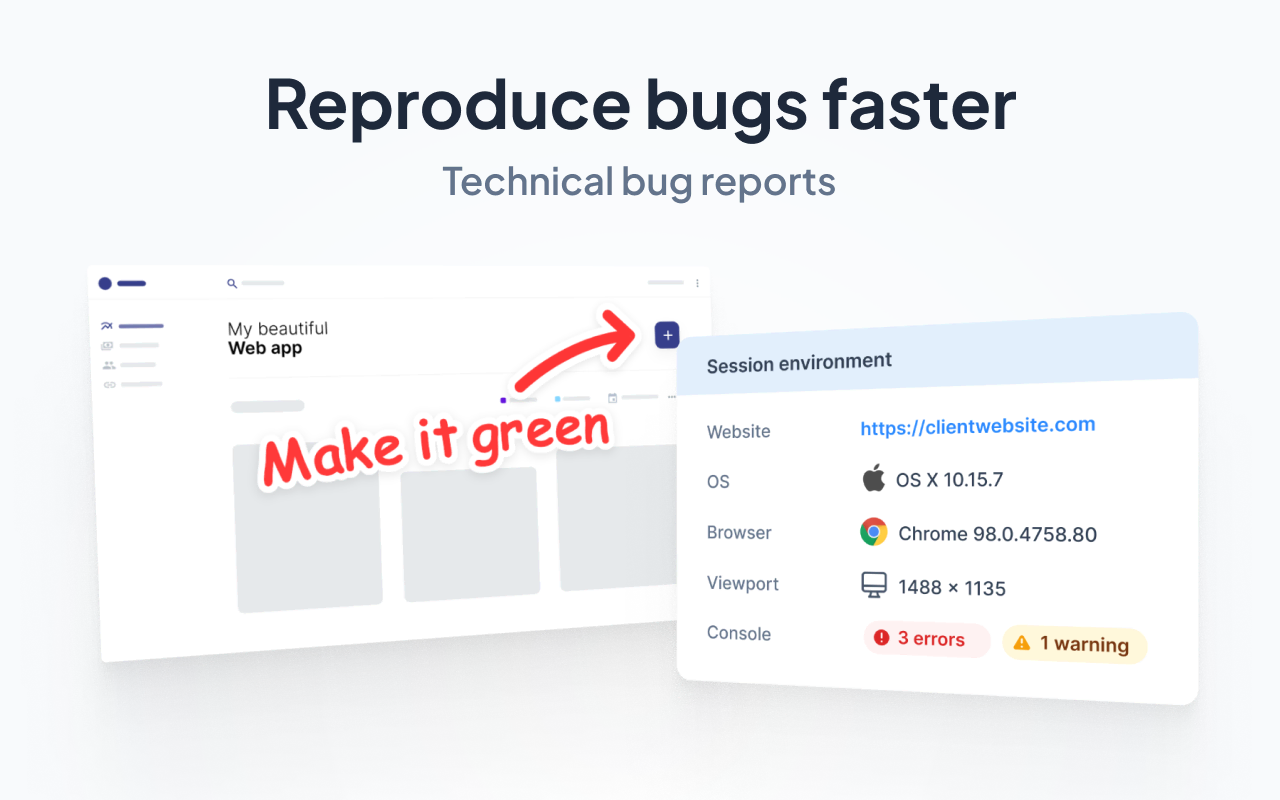

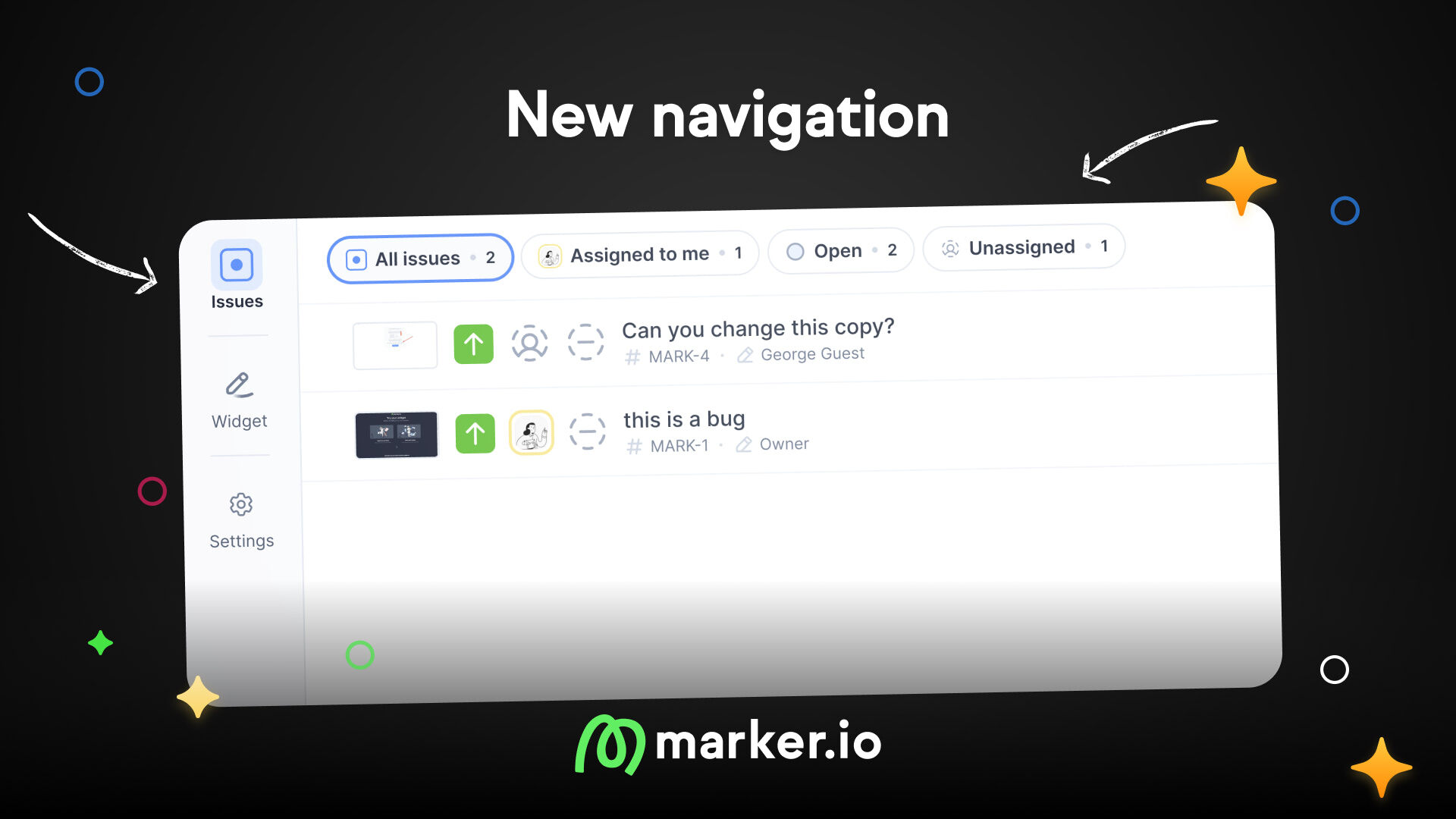

4. Marker.io: While Marker.io is not a test case management tool per se, it complements these workflows. It helps you and the team report bugs and in a complete way.

For example, when a test case fails, your quality assurance team, clients and actual users can use Marker.io to take screenshots (which automatically collects console logs, environment details, and metadata).

This helps your testers report faster without losing context into the actions they took that made the test fail. It also reduces back-and-forth between testers and developers as developers have all the context they need upfront, including a 30 seconds playback video.

Benefits of using a test management tool:

- Version control: You can track changes to test cases over time and keep historical records.

- Reporting: You can generate dashboards that show pass/fail rates, test coverage, and defect density.

- CI/CD integration: Connect test execution with your build and deployment pipelines to support continuous testing in agile workflows.

Final thoughts

Good test cases are clear, reusable, and effective. They tie directly to requirements, provide exact steps and input data, and have specific expected results. When designed this way, your test cases will help testers test fast and help developers debug faster.

I’ve also explained some of the best practices of writing test cases and the tools to manage all your tests. All these can help you avoid mistakes in your process and create a reusable and lean test suite.

What should I do now?

Here are three ways you can continue your journey towards delivering bug-free websites:

Check out Marker.io and its features in action.

Read Next-Gen QA: How Companies Can Save Up To $125,000 A Year by adopting better bug reporting and resolution practices (no e-mail required).

Follow us on LinkedIn, YouTube, and X (Twitter) for bite-sized insights on all things QA testing, software development, bug resolution, and more.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is Marker.io?

Who is Marker.io for?

Marker.io is for teams responsible for shipping and maintaining websites who need a simple way to collect visual feedback and turn it into actionable tasks.

It’s used by:

- Organizations managing complex or multi-site websites

- Agencies collaborating with clients

- Product, web, and QA teams inside companies

Whether you’re building, testing, or running a live site, Marker.io helps teams collect feedback without slowing people down or breaking existing workflows.

How easy is it to set up?

Embed a few lines of code on your website and start collecting client feedback with screenshots, annotations & advanced technical meta-data! We also have a no-code WordPress plugin and a browser extension.

Will Marker.io slow down my website?

No, it won't.

The Marker.io script is engineered to run entirely in the background and should never cause your site to perform slowly.

Do clients need an account to send feedback?

No, anyone can submit feedback and send comments without an account.

How much does it cost?

Plans start as low as $39 per month. Each plan comes with a 15-day free trial. For more information, check out the pricing page.

Get started now

Free 15-day trial • No credit card required • Cancel anytime